How Americans' Access to Credit is Perpetually Discriminatory

From Redlining to FICO Scores

By Adam Bozman

May 26, 2022

Introduction

Conceptually - at least, it seems to make intuitive sense - risk, or risk assessment rather, has become essential to contemporary business practice(s) and international economic policy. Naturally, the concept of risk (in its many manifestations) spans all corners of finance – still, it seems to unequivocally dominate consumer lending. A financial pillar, if you will, consumer lending has developed as much as any aspect of financial exchange in our country’s brief history. What’s more, these evolving practices have lasting implications for all consumers. This blog post discusses how federal policy has shifted in the last century with regard to consumer lending, and how these contemporary policies may still disproportionately affect certain individuals.

Foundation of HOLC and The New Deal(s)

In the aftermath of the Great Depression, the U.S. government set out to evaluate the riskiness of mortgages – and left behind a stunning portrait of racism and discrimination that has shaped American housing policy. It wouldn’t be possible to discuss 21st century lending practices without acknowledging the 20th century’s blunders, this last 100 years simultaneously advocated for and undercut movements of standardization, regulation, and inclusion.

FDR’s New Deal meant to respond to the burdening pressures following America’s Great Depression, and in many respects it did. New infrastructure, new jobs, and more security were all on the docket. Coming in two parts (First New Deal 1933-1934/Second New Deal 1935-1936), the first iteration preached reform, fiscal policy, banking reform, and the Securities Act of 1933, following the crash of Wall Street in 1929. Meanwhile, the second iteration emphasized things like social security, labor relations, and jobs creation. The now infamous Housing Act of 1934 outlined things like the FHA (Federal Housing Administration) and the HOLC (Home Owners’ Loan Corporation) – the creator of the ‘residential security map’ – today referred to as redlining.

FDR’s quick actions sparked criticism, namely claims of fascism and communism. Although the 1930s were a time that any federal intervention would’ve likely been met with similar animosity. Nearly a hundred years later, a different criticism is common – discrimination.

‘Residential Security Maps’

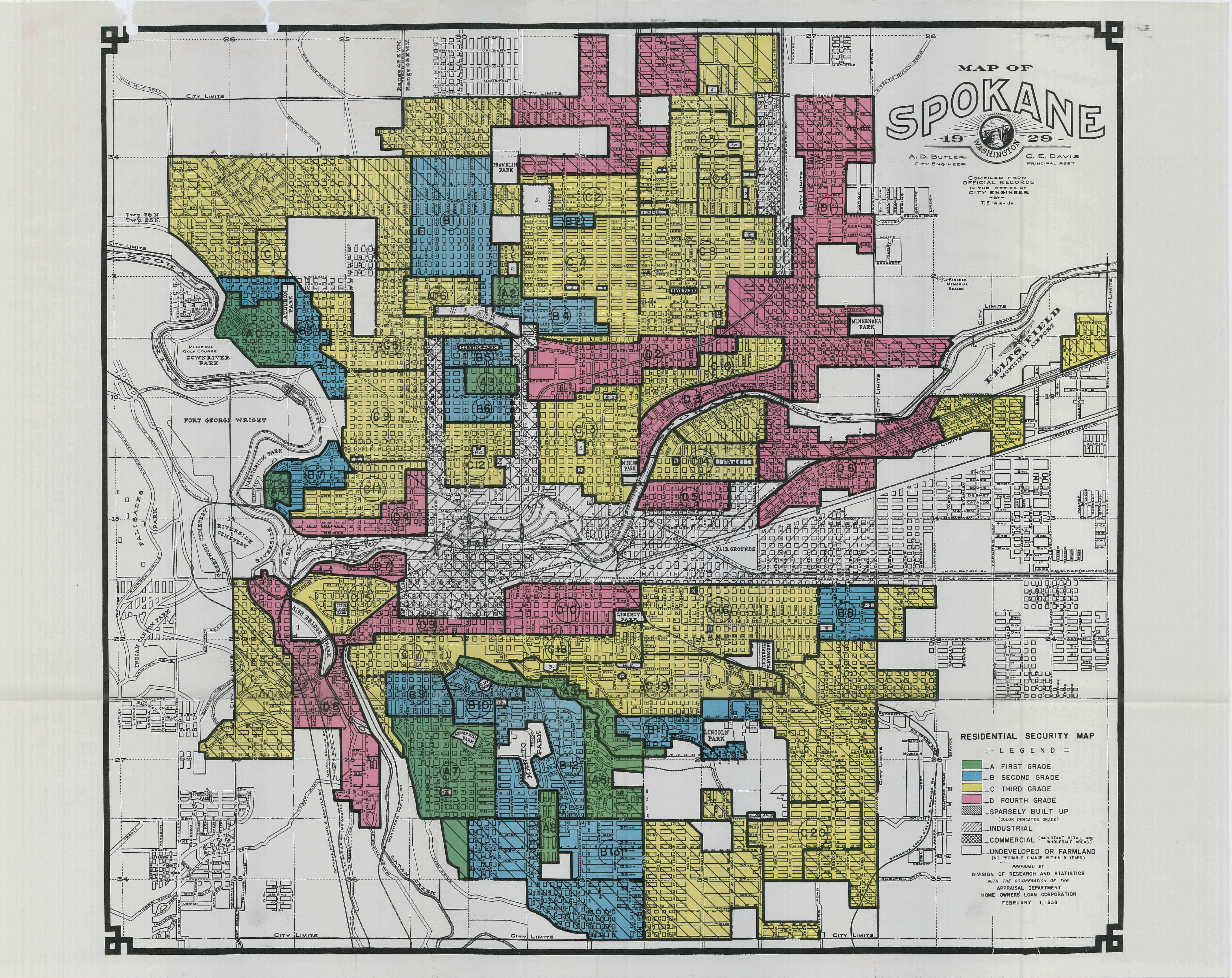

In brief, ‘residential security maps’ of 239 cities were initially created to indicate the level of security for real-estate investments in each surveyed city. These maps consisted of four key markers:

Type A (Green): Typically the affluent suburbs surrounding metropolitan areas

Type B (Blue): Similar areas, generally more urban but considered ‘still desirable’

Type C (Yellow): labeled as ‘declining’

Type D (Red): Urban neighborhoods outlined in red and considered the most risky for mortgage support and development opportunities

In some cities these ‘Type D’ neighborhoods were still majority white, but these same neighborhoods were home to the vast majority of the African American households, by proportion in the respective city. Recent controversy has erupted, citing that the HOLC did not redline in its own lending practices, pushing the responsibility of racist language and reflected bias on the private sectors and those experts hired to conduct appraisals. This language translated upstream to prominent private organizations, like appraiser J.M. Brewer and others that designed maps to meet the requirements of the FHA’s underwriting manual. A number of these private organizations still in operation have received fines and penalties in the previous years.

Regardless, it is impossible to either ignore or overemphasize the impact this had on minority neighborhoods in the middle of the 20th century. It is estimated that between 1945 and 1959, African Americans received less than 2% of all federally insured home loans. This would ultimately result in both less lending available to these neighborhoods and residents pursuing predatory lending practices (more on that later).

Redlining has gained infamy in recent years as more transparent American history is discussed, but I think many still envision it as an abstract concept - something only applicable to places like Chicago or New York. To be certain, this abnormality directly impacted 239 cities. I include an residential security map of my home town below, Spokane. Spokane is still considered a small-medium sized city in eastern Washington. At the time of this maps creation, it was considerably smaller relative to other developed areas. This map comes from faculty at the University of Richmond - they have compiled a fantastic list of all redlined cities in the 20th century, available here.

Transitioning in the 1970s

It is important to include policies that came about decades after the HOLCs inception and officially cease of operation in 1951. Many of these were, in essence, band-aids. Nevertheless, I include them here:

Fair Housing Act (FHA)

Lyndon B. Johnson passed the landmark ‘Fair Housing Act of 1968’, also referred to as ‘Civil Rights Act of 1968’. Among other things, this act was passed to fight the practice of redlining.

The Fair Housing Act makes it unlawful to discriminate in the terms, conditions, or privileges of sale of a dwelling because of race or national origin. The Act also makes it unlawful for any person or other entity whose business includes residential real estate-related transactions to discriminate against any person in making available such a transaction, or in the terms or conditions of such a transaction, because of race or national origin.

Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA)

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act, enacted October 28th, 1974 and codified into law, makes it unlawful for any creditor to discriminate against any applicant (with respect to any aspect of a credit application) on the basis of race, skin color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, or age. The law applies to any person or entity who, in their ordinary course of business, regularly participates in credit decisions (e.g., banks, retailers, credit card companies, other financial institutions, and/or credit unions). Regulation “B” designates the authority and scope of ECOA – failure to comply may result in punitive damages of $10,000 in individual actions and the lesser of $500,000 or 1% of the creditor’s net worth in class actions.

Community Reinvestment Act (CRA)

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) reemphasized this notion of ECOA – it charges all financial institutions with applying to the same equal lending criteria to all areas within which they are chartered. The Act mandates that all banking institutions that receive Federal Deposit Insurance Corporations (FDIC) insurance be evaluated by Federal banking agencies. This now applies, similarly, to the National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund (NCUSIF).

Steps were taken in the right direction, but like any process of standardization, breadth and inclusivity are often negated for efficiency.

Credit Scores and Standardization

A decade later, following the slew of regulations targeting residential lending, modern credit reporting came to be. The first-ever credit bureau-based FICO credit score became commercially available in 1989 through Equifax. Vantage Score wasn’t introduced until 2006.

To be sure, the concept of credit reports existed before this – only in a logistically very different way. Prior to 1989, merchant associations collected and sold credit information about borrowers from local sources, called subscribers. Many of these merchants were born in the late 19th century and, through mergers and consolidation, still exist today while operating in a different capacity (e.g., Dun & Bradstreet).

Early credit reporting was often unfair and subjective, as we’ve seen. After congress passed FCRA, consumer protection laws moved to center stage. A few of these important protections:

- Credit reporting time limits on negative information

- The right to dispute information on a consumer report

- Permissible use limitations

- Credit freezes

- Free access for consumers

By the mid 1990’s, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac began requiring lenders to use FICO scores on residential mortgage applications. This followed specialized scoring that FICO scores were assigned to in 1993 (e.g., bankcard, auto, personal, mortgage).

Systemic Discrimination

Moving past the fact that FICO scores were based of the logic of two white men (Bill Fair and Earl Isaac) in 1956, the financial activity that credit agencies use(d) in scoring is inherently based on financial instruments that have not traditional been available to minority communities. It is, in essence, a cyclical process. Now, we are getting into an entire branch of economic racism that I would like to avoid. Not that this isn’t important, but the goal of this writing is to focus on tangible policies and their affect – as opposed to the more informal and inherent biases in policy making (this is worthy of an entirely different discussion).

Nevertheless, it is crucial to highlight that most credit score calculations are based on payment history and credit use – something that most minority populations have very little exposure to. Per capita, lower rates of home ownership, higher average interest rates, and less credit usage historically all propagate this disparity. Frederick Wherry, a Princeton sociologist who studies financial racism, told Forbes, “It’s a mirror of inequalities from the past. By using this data we’re amplifying those inequalities today. It has a striking effect on people’s life chances.”

Racial Wealth Gap

While referring to the difference in assets owned by different racial or ethnic groups, this gap results from many of the economic factors already discussed. The term reflect disparities in access to opportunities, means of support, and resources.

Generational Wealth

The easiest manifestation of this remains in home ownership – historically, the primary driver of generational equity. Naturally, this inequity stems directly from discriminatory practices within redlining and FICO lending, even if indirectly.

Federal Reserve of Chicago

The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago released a report by several of their economists (Aaronson et al.). In this they study the effects of redlining maps on long-run trajectories of neighborhoods. Using boundary design and propensity scoring, they found that the redlined maps led to reduced home ownership rates, house values, and increased racial segregation in late decades. They conclude that the HOLC maps had “meaningful and lasting effects on the development of urban neighborhoods through reduced credit access and subsequent divestment.”

I should mention that Dr. Frederick Wherry (alongside Kristin Seefeldt and Alvarez Alvarez) find similarly shocking effects with respect to Credit Scores and contemporary lending practices in the book, Credit Where It’s Due: Rethinking Financial Citizenship.

Contemporary Issues

While steps have been taken, lending discrimination still exists today – notably found in traditional access to financial services, real estate development, and even student loans - Educational Redlining. However, some high-profile repercussions have emerged. Perhaps the most notable was in 2019 when the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) charged Facebook with violating the FHA – because the company’s advertising platform let real estate agents target potential renters and home buyers based on race, religion, gender, and disability status. As a former marketer, I’m relentlessly intrigued on how this new access to seemingly infinite customer demographic data will shape business practices and policy decisions in years to come.

Lending Discrimination and the Opiod Epidemic

Recently, a colleague of mine published work on how Payday Lending and the Opioid Epidemic are interrelated, suggesting that household finance regulations can impact societal health. Naturally, endogeneity issues arise when discussing discriminatory lending and societal health. Nonetheless, the relationship between nontraditional lending sources, predominantly minority neighborhoods, and societal health undoubtedly exists – teasing out the root cause of these confounding stresses will be the challenge.

To what extent has segregation been rebranded as discriminatory lending?

Philosophical and Ethical Implications

This of course prompts a philosophical question – how can any individuals’ access to credit be determined in an objective, unbiased way? Try as we might – it seems to be a challenge. Moreover, what weight does a poor - albeit objective - credit score truly carry to those that better understand their nuanced weaknesses (e.g., individuals that file bankruptcy – statute of limitations – or those that file chapter 11 under a corporation). This point touches again on the idea of educational redlining, something altogether deserving of another discussion – how access to opportunities, by race or proximity, enables progress.

This topic isn’t necessarily something of a foundation for future research. Rather, it is just something I care about, something I think is important. Any suggestions of further reading or constructive criticism are always welcomed

- Posted on:

- May 26, 2022

- Length:

- 10 minute read, 2001 words

- See Also: